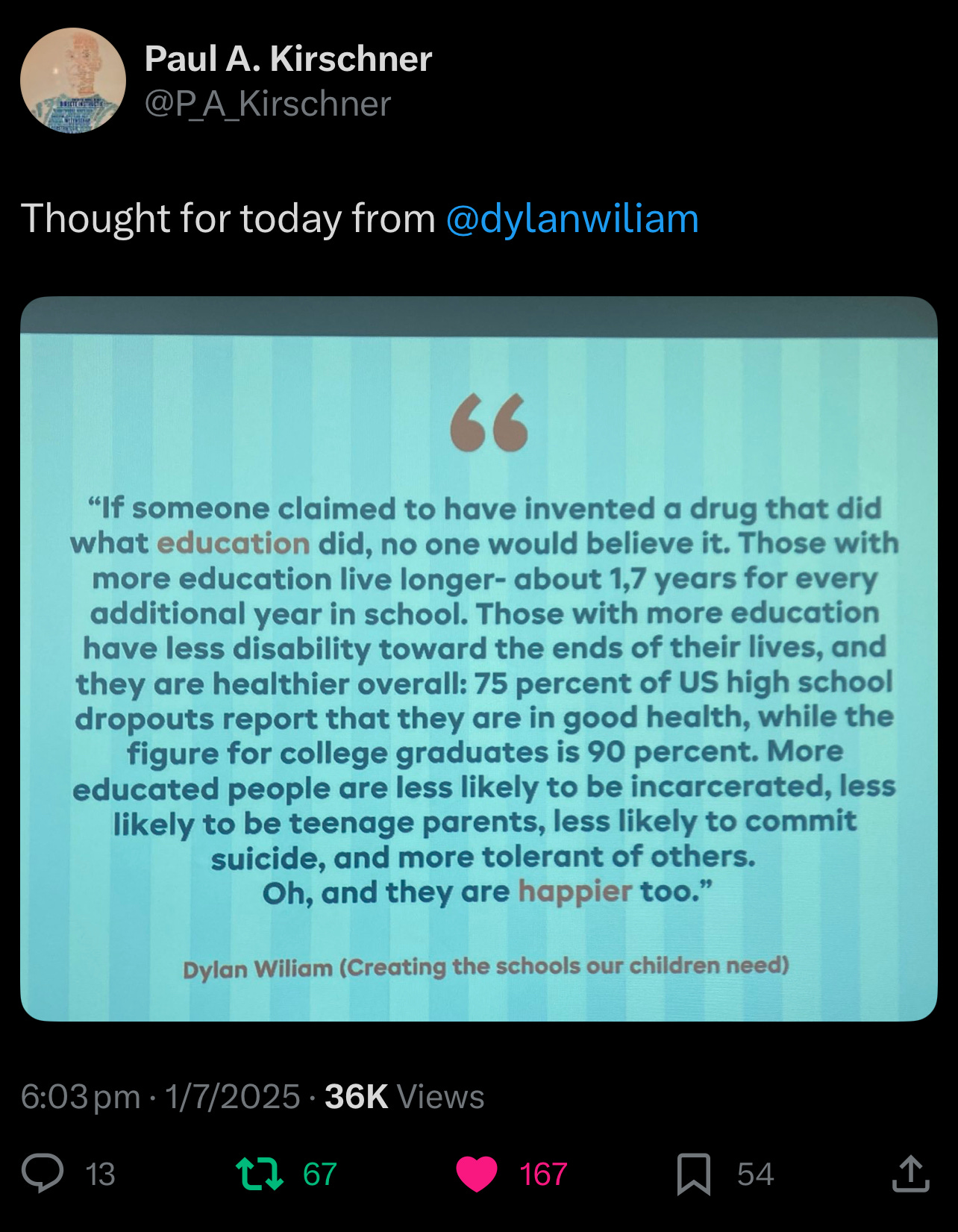

Paul Kirschner, the distinguished educational psychologist, posted a quote from Dylan Wiliam, the famous education researcher, on Twitter/X and some people lost their minds:

What’s wrong with suggesting that people with more education tend to live longer or are less likely to be incarcerated?

Ostensibly, this is an argument about correlation not being the same thing as causation. Wiliam’s quote implies that education causes these positive outcomes—like a drug—but it is possible they are merely correlated. For example, wealthy people tend to spend longer in education than poorer people and it may be their wealth that causes them to live longer, not their education.

This is a reasonable point to debate. However, from the outset, it’s worth noting that this can never be resolved beyond reasonable doubt with a randomised controlled trial because it would be unethical to randomly assign young people to receive different amounts of education. In a sense, this is similar to the evidence for smoking and cancer. We can’t do randomised controlled trials to test that relationship either, so how are we so certain?

When we have enough correlational evidence, we can tentatively start to test it for causation. For instance, we can compare individuals from backgrounds with similar levels of wealth and different amounts of education. However, biases may remain and we cannot control for every possible factor.

This is where natural experiments and, in particular, regression discontinuity designs come in. A population may suddenly have a new policy imposed on them—such as to extend the number of years of compulsory schooling—and we can look at trends just before and just after its introduction. Or, we can examine similar populations subjected to different policies.

There is lots of evidence of this kind for the effects of education. To take just one example, Adriana Lleras-Muney looked at U.S. census data and various compulsory education laws to determine that more education reduces mortality rates.

Add in a coherent theory and triangulate with converging evidence from slightly different fields and we can build a pretty compelling case.

Ultimately, however. you may not find this correlational evidence convincing and that’s fine. If so, you are probably also sceptical of the smoking-cancer hypothesis and the greenhouse gas emissions-global warming hypothesis. That’s not a mistake, as such, but a difference in perceptions of evidence.

Nevertheless, one clear mistake people do make when considering this sort of data is to misunderstand averages. If we do accept that education has positive effects then these work on average. We might, for instance, expect the average age of mortality of 1000 people with a university education to be higher than that of 1000 with a high school education who did not attend university. It does not mean that guy you know who studied classics and drinks Stolichnaya and smokes cigarettes in the dark all day will outlive your gym bunny friend who never went to college.

Stepping back a little, what does even the existence of this debate mean? Isn’t it a little weird that people who appear to be involved with education would be so furious at Kirschner/Wiliam for suggesting their work has value? What’s all that about?

Well, if the thread is our guide, it seems to come from a decadent latter day reading of left wing politics. I assume that the reasoning is something like this: If we accept that education has positive effects this will then let governments off the hook for addressing deeper issues such as poverty, racism and other forms of disadvantage and/or injustice that hold people back. Governments can look to the disadvantaged and declare that all they need is an extra year of school and that’ll fix them.

The founders of the labour movement would find the view that education is a distraction from deeper issues shameful. They valued education and were often involved in bringing its benefits to the poor. They knew that wealthy countries are quite capable of walking and chewing gum at the same time.

Moreover, they demanded it of their politicians.

The point of averages is extremely important. I always hear from kids (and also some adults) that "so-and-so billionaire dropped out of college and look how successful they are!" Yeah, and some daily smokers live to be 100 years old. The point is that they are one in a billion in their luck. Though I will say, I got a good laugh about it once -- one time I explained this whole life expectancy thing to my senior students (12th grade), and a kid said "don't you have a master's degree?" "Yes," I said. "Well but...what if you walk outside right now and get hit by a bus?" With an n=1, I guess that would mean that having a master's degree makes bus-death more likely...

Good points, Greg. We need a sensible jargon for times when heaps of correlations point the same way. A common term is 'strong inference' which can imply the judgement of 'provisionally correct.' I suspect that would be a red rag to some bulls. My suggestion is 'PLAUSIBLE INFERENCE' Should anyone tut-tut about that term, then a suitable response might to ask them for empirical evidence that points to weak inference, or none.