Peter Liljedahl, the Canadian professor who made up an approach to teaching mathematics known as ‘Building Thinking Classrooms’, is not a fan of ‘mimicking’.

Here he is, featuring in a 2024 article for KQED by Kara Newhouse:

“The ‘I do, we do, you do’ approach is a common teaching strategy in math classrooms. In it, a teacher demonstrates how to solve a certain type of problem, the class practices as a whole, and students practice independently. But Liljedahl said, ‘There’s nothing about that environment that prepares students for all of a sudden me saying, “Well, here, let me show you this property. Now figure out what this is,” because all of their habits are around mimicking. And this is a problem because if students are not thinking, they’re not learning.’”

If you follow the link in that passage, it takes you to an article on inquiry learning that argues we should flip the order and start with ‘you do’. That’s because ‘I do, we do, you do’ is a succinct way of describing explicit teaching, the opposite of inquiry.

As the Australian Education Research Organisation (AERO) explains:

“A common and flexible framework for explicit instruction involves an ‘I do, we do, you do’ approach. The teacher introduces new content (I do), then works together with students, often with several repetitions for guided practise (we do), before students work in pairs or individually, supported by teacher observation and support (you do).”

Liljedahl is not a fan and that’s OK. He can make his case and present his evidence, and we can do the same.

In a 2023 interview with Jennifer Gonzalez for Cult of Pedagogy, Liljedahl explains that in his view, mimicking is not thinking:

“In a traditional classroom… we show the students how to do it, then we do one together, then they practice it on their own, the classic I do, we do, you do, which promotes — whether you want it or not — a form of behavior called mimicking. So these students are just going to mimic their way through. In a Thinking Classroom, in order to get students to think rather than mimic, we have to remove the I do.”

I wholeheartedly disagree with this point on two different levels. Firstly, a student applying a method a teacher has modelled for them to a different mathematics problem will literally be doing a lot of thinking. If we hooked them up to a brain scanner, I would predict we would find lots of activity. Mathematics is hard and unnatural and so for a novice learning a new method, this requires a lot of processing.

I also disagree with the implication that thinking hard is always a good thing. Cognitive resources are limited and so if we just ‘know’ that 8 x 7 = 56 we can deploy those resources to some other aspect of the problem. This is why we want students to achieve fluency, not just with maths facts such as these, but with many procedures such as rearranging equations, factorising expressions and so on. In this context, Liljedahl’s ideas are completely misconceived.

But, again, he is entitled to his views and to be able to make his case.

Thankfully, from my perspective, Australian states are starting to move away from inquiry-based teaching that eliminates the ‘I do’. A great example of this is the new pedagogical framework launched by Tasmania’s Department for Education, Children and Young People (DECYP) which references the work of AERO.

The framework is tremendous. One key strategy outlined in it is ‘explicit instruction with gradual release’ which makes clear that the authors are writing about explicit teaching as an instructional sequence and not just an episode of explanation. However, on the subject of explanations, it states:

Teachers chunk complex concepts, strategies, or skills and break up intended learning to optimise working memory.

Teachers intentionally sequence learning to manage students’ cognitive load and build skills gradually (e.g. less difficult skills then more complex skills).

Teachers present information clearly and explicitly in small chunks, with explanation, demonstration and modelling.

Teachers introduce new skills in isolation then integrate with other skills and scaffold learning by building in support and extension.

[my emphasis]

Isn’t that great? Of course, it is the kind of teaching that Liljedahl would criticise for leading to ‘mimicking’ but that’s OK. Liljedahl and the Tasmania DECYP may disagree. We’re all grown ups.

But wait. What is this that a sleeper agent buried deep within the Tasmanian education system has been sent?

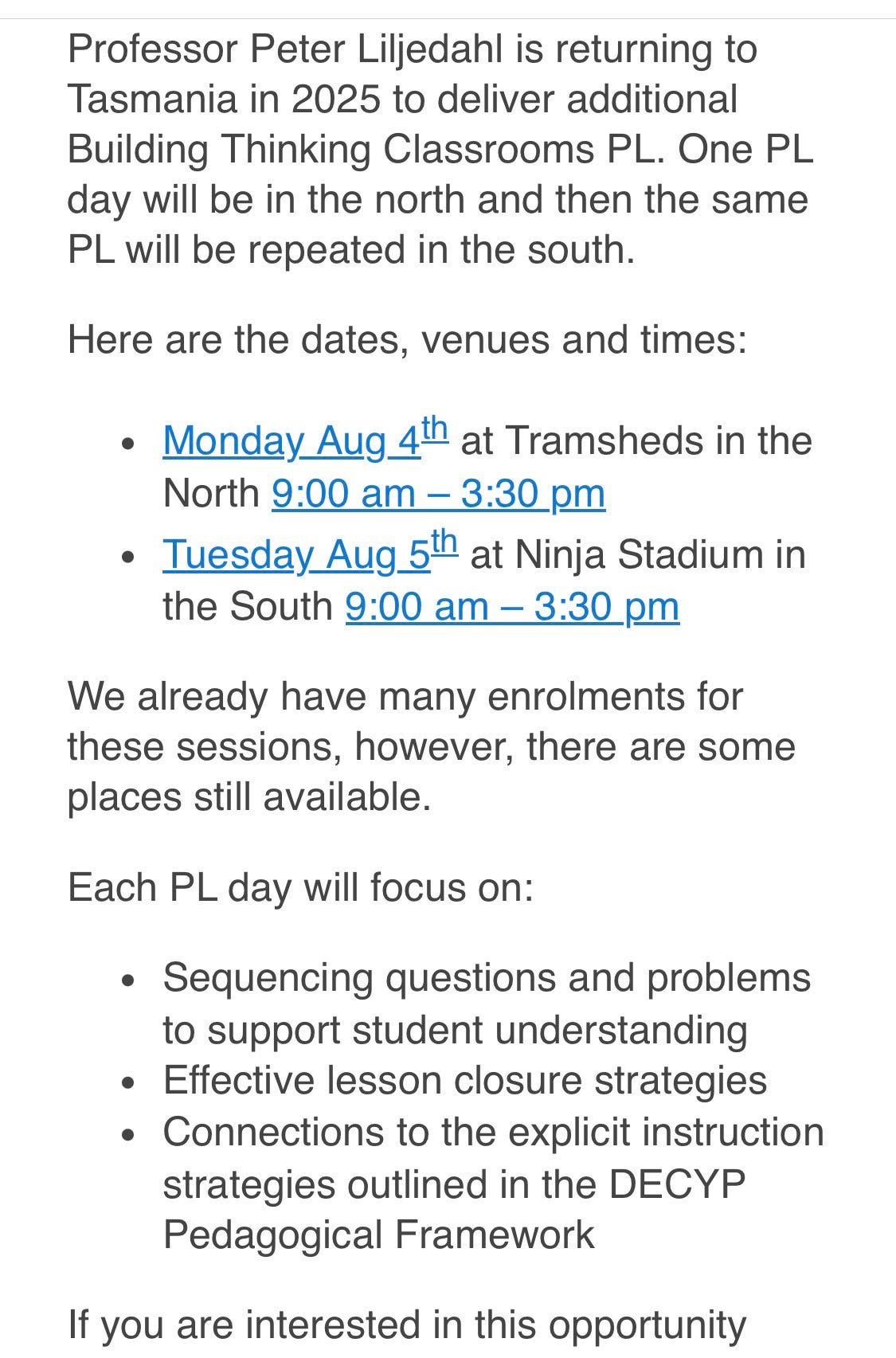

What’s that? Peter Liljedahl will focus on connections between Building Thinking Classrooms and the explicit instruction strategies outlined in the DECYP Pedagogical Framework?

That’s like hiring Greta Thunberg to promote a new line of diesel SUVs.

I think they’re a little confused.

I wonder if Liljedahl has advertised his session in this way, knowing that’s what’s expected by the Tasmanian government or if the people who have arranged for him to come have advertised it this way for the same reason. My guess is the latter, but someone who attends the session should ask him to share the explicit instruction techniques as advertised and report how that turns out.

No Greg,

It’s like having Darren Wayne Woods, CEO of ExxonMobil, promote fossil free energy programmes.