Something changed

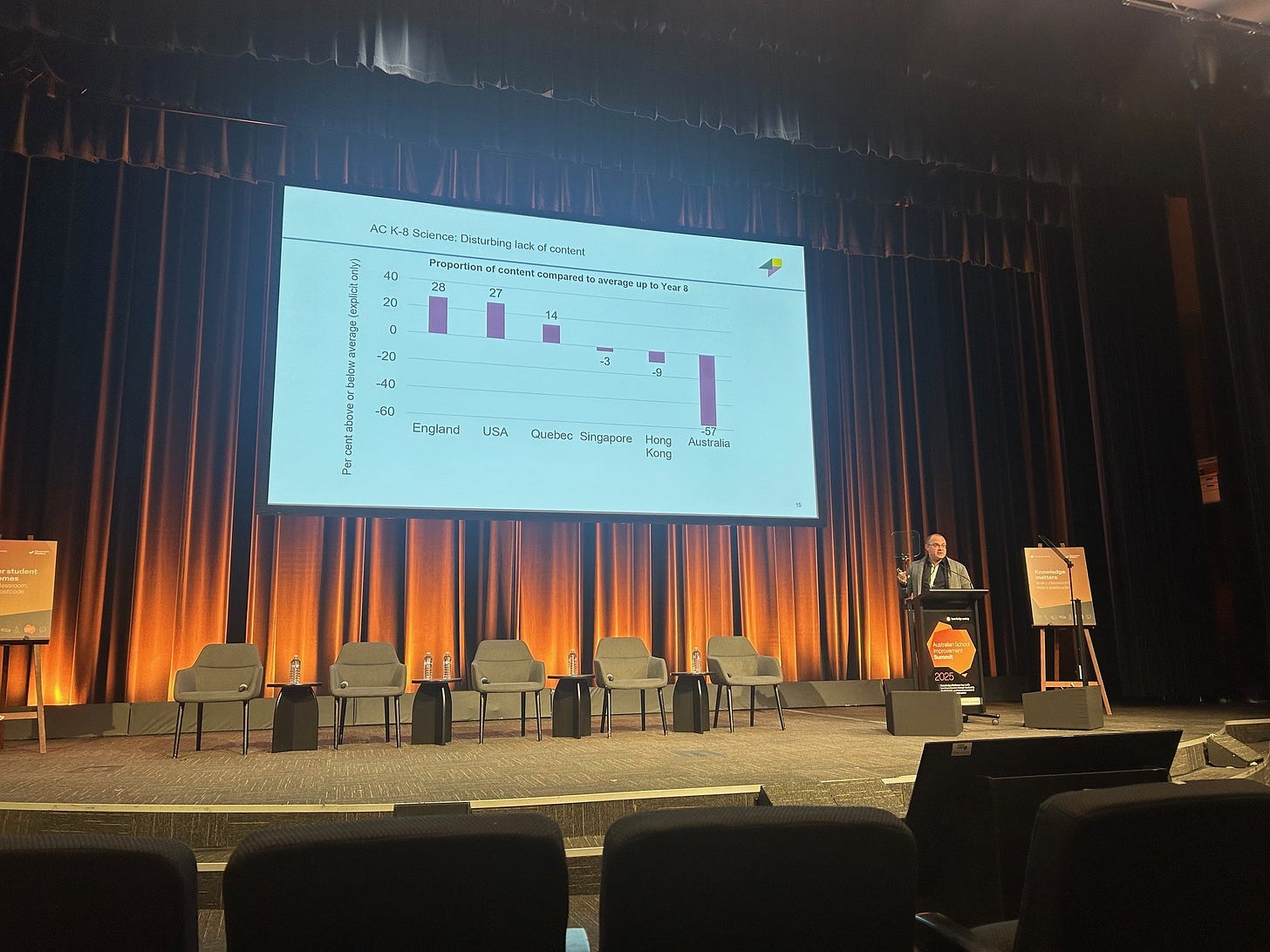

A day at the Australian School Improvement Summit

For less than the cost of one cup of coffee per month, you can be a full subscriber to Filling the Pail with complete access to all of the extensive archive on a range of topics, as well as access to the unabridged version of my weekly Curios posts.

Yesterday was the second time I have attended the Australian School Improvement Summit organi…