After leaving Bright and the glory of Mount Buffalo, this week has seen a return to work with the start of Term 3. It has been distinctly wet in Ballarat and that’s a good thing, with the farmers thankful to fill up their dams. I have picked up a Year 6 science class — I am teaching the current physics topic on sound and hearing and then the boss will take over again for immunology. Which reminds me, if anyone knows any science teachers who are at a loose end right now, please get in touch or ask them to complete an expression of interest here.

In the meantime, Year 6 science is good fun. We have learned about sound waves, amplitude and frequency, and a neat trick for figuring out how far away a thunderstorm is by counting, in “baby elephants,” the time between the flash of lightning and the roar of thunder.

This week’s Curios include some pointless research, a rockstar maths teacher, not one, but two, Nazi comparisons, and much more.

Furore of the week

Regular readers will be familiar with Phil Beadle’s grumblings about education in England and what he perceives as some kind of authoritarian takeover. I recently wrote about the fact that he complains about being labelled educationally progressive while at the same time, and without apparent irony, labelling his opponents ‘totalitarian’.

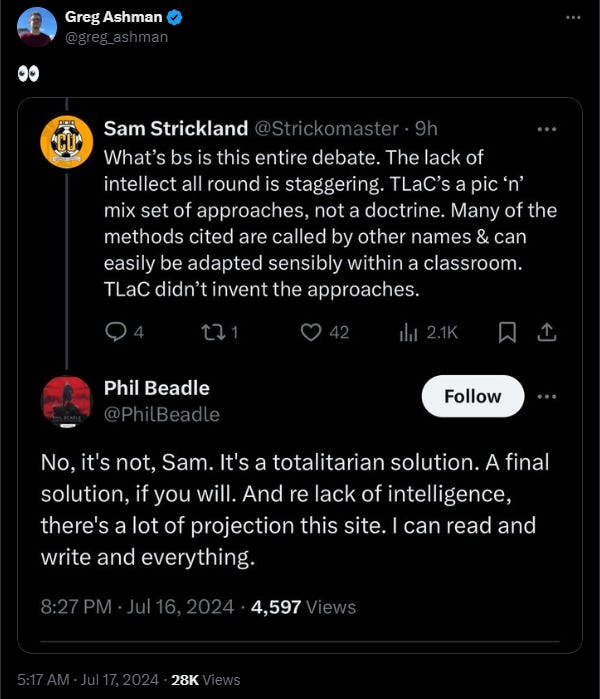

However, this week, Beadle took things further:

TLaC stands for Teach Like a Champion, a set of strategies Doug Lemov derived from observing expert teachers. The context is a discussion of cold calling — a teaching strategy promoted by Lemov and others in which students are called on to answer a question in class without raising their hands and volunteering. Is cold calling like Hitler’s ‘final solution to the Jewish question’ and the mass murder of six million Jews? No, and trivialising the holocaust in this way is offensive.

When I shared the comment on Twitter, Alex Pond noted this is not an isolated case. Beadle has apparently made this comparison three times.

Jane Prinsley of The Jewish Chronicle got hold of the story and published a piece that must have left regular readers, unfamiliar with EduTwitter, scratching their chins in bemusement. As a result, Beadle has now walked back a little, suggesting the analogy was clumsy. However, as of the time of writing, he has not deleted his Tweet and has doubled down on insisting that Teach Like a Champion is “borderline fascistic.” Which is bonkers.

Although I do not share their concerns, I feel sorry for those who are genuinely critical of approaches such as cold calling and others described in Teach Like a Champion. It must be frustrating to line up alongside people so set on stoking a culture war.

Pointless research of the week

Haley Tancredi and two other education academics have written an article for The Conversation, suggesting teachers talk too much. I cannot be certain, but from the information available online, it looks like none of them have ever been teachers themselves. So, we could treat this as just another potshot at the profession from those outside.

However, if we dig a bit deeper, the research presented provides an illustrative case study. The researchers interviewed 59 students with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) or Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Their conclusions about teachers seem to be based on the fact that two-thirds of those interviewed agreed that their teachers talked too much. If we look at the study itself, we can see they determined this by asking the leading question, “Do you think some teachers talk too much?” and giving the options, “Yes/No”.

Given they asked whether only ‘some’ teachers talk too much, it’s strange they didn’t obtain a response closer to 100%.

What are we to make of it? Not much. If the researchers were interested in the differential impact of teaching methods on students with DLD and ADHD then why did they not interview students from a control group who do not have these disorders? The implication is this finding is specific to these students, but 69% or more of students without these disorders may have answered the same.

And how do they know whether students can accurately judge whether a teacher talks ‘too much’? The response is going to be based on student preferences and these may or may not coincide with the most effective forms of teaching. We have known since at least as far back as the Dr Fox experiment that students are not great at evaluating the effectiveness of teaching. As a research method, it is close to meaningless. However, such research is relatively cheap and easy to do and gives the researchers cover to pontificate at length about these terrible teachers who talk too much.

What should teachers do? According to the researchers:

“There is no precise figure when it comes to the amount a teacher should talk, but a good rule of thumb is around one quarter of the lesson. This allows time for active questioning and feedback, and for the completion of activities. It also reduces student passivity and is less exhausting for the teacher.”

The link in the passage to support the ‘rule of thumb’ does not take us to peer-reviewed research but to a 2019 opinion piece in EdWeek. This does not appear to mention the ‘one quarter’ figure, so we reach a dead end.

In the real world of actual classrooms, it is silly to set such arbitrary limits on something as variable as teacher talk. It will depend on what the talk is about. A teacher going off on tangents will be counterproductive when the students need to practice what they have just been shown, even if it is just for a minute or two, whereas a history teacher captivating students with the story of a great battle could talk fruitfully for an extended period. And from the way they have phrased it, it seems the researchers see ‘active questioning’ as something quite different to teacher talk, but teachers often use talk to ask questions. 🤷♂️

If we want a better handle on talk in classrooms, we would do well to heed the process-product research of the 1960s-70s. This involved observing classrooms and finding correlations between teacher behaviours and student learning gains. It is this body of research that is the foundation for Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction. The same research is explored in more detailed in a 1984 article by Jere Brophy and Thomas Good. They found that what they termed ‘active teaching’ was associated with higher student learning gains and they describe what this looks like:

“The teacher carries the content to the students personally rather than depending on the curriculum materials to do so, but conveys information mostly in brief presentations followed by recitation or application opportunities. There is a great deal of teacher talk, but most of it is academic rather than procedural or managerial, and much of it involves asking questions and giving feedback rather than extended lecturing.” [My Emphasis]

Not only is process-product research more rigorous than the ask-a-bunch-of-kids method, it’s far more useful to practising teachers.

Motivational finding of the week

Lots of people buy in to folk myths about motivation, but the truth is more interesting and gives grounds for optimism.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Filling The Pail to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.