Sunday was Mothers’ Day in Australia and so we went off to the Yacht Club for a breakfast. It was a beautiful, sunny autumn day as we walked past the boathouses. The lake has featured in the last two Curios because it is such a great time of year for it when the Sun is relatively low in the sky.

This week also saw Australia’s treasurer, Jim Chalmers, hand down the federal budget. As such, it was the first budget during my newfound role as an economics teacher and so we had to discuss it. The part that left us all scratching our heads was the manoeuvre where Chalmers plans to given money directly to energy companies to reduce our bills by $300 and the apparent intention of this move to reduce inflation. Yes, energy prices are in the ‘basket of goods’ that economists use to calculate inflation and so you can see the logic, but isn’t this a dodge? How can putting money into the economy curb inflation? My economics knowledge is still a work in progress.

This week’s Curios include a ultracrepidarian, some worrying signs, educational academics in favour of ‘zero-tolerance’ and much more.

Ultracrepidarian of the week

An ultracrepidarian is a ‘cobbler who passes judgement beyond the shoes’. In other words, it is someone who spouts forth, often at great length, on subjects outside their area of expertise. The rich and famous are particularly prone to it because they tend to surround themselves with lackeys who fawn over them and never tell them they are wrong. At the pinnacle, sit billionaires.

I am not one of those who think Elon Musk is a bogeyman. He is a typical billionaire. I am impressed by the work he has done building an electric car company and a space business and, perhaps more controversially, I admire his public-spirited purchase of Twitter, ostensibly to protect free speech. However, I do not agree with him on everything.

One of those areas of disagreement are his untutored views on education. Reporting on a speech Musk recently gave, Christiaan Hetzner in Fortune magazine writes:

“‘You don’t want a teacher in front of a board,’ the serial entrepreneur and Tesla CEO argued during a discussion on Monday with Michael Milken that otherwise veered heavily into the existential risk facing humanity.

Kids instead need compelling, interactive learning experiences that engage them with subject matter, such as taking apart a car engine to understand how it works and, in the process, learning what wrenches and screwdrivers are used for.”

I wonder if Musk thinks he is the first to make such a commonplace, but deeply misguided, observation. Yes, from the vantage point of someone who was probably a gifted student, the idea of a child being able to work on passion projects through which they discover fundamental ideas seems appealing. However, rolling out such approaches at scale will fail.

This has been the promise of educational progressivism for well over a century and one it has failed to deliver on.

Pompous Canadian professor of the week

Steve Joordens, a Canadian psychology professor previously best known for the unique way he once began a lecture, went to a researchED conference in Toronto and did not quite approve. You can read his assessment on LinkedIn. The introductory paragraph is typical:

“I recently attended to the #researchED conference held in Toronto and did so with deep curiosity. Having considered myself one who believes heavily in the science of learning and in evidence-based educational practice, I had heard controversy around the way this group was using, and in fact taking possession of, those terms which should be just what they say they are and nothing more. In fact, I had heard that they are in fact bringing politics into the process of educational enhancement, something I simply had not encountered in my years of doing educational research. I attended almost as an anthropologist visiting this unique grouping of humans to see what they were all about, and if the controversy associated with them is deserved. What follows is my impressions, which of course are subjective. Perhaps this will seed an interesting conversation.”

As I noted on Twitter, when I read this delightfully pompous piece, I imagined the voice of the fictional Dr Frasier Crane.

Has Joordens really never encountered politics during years of doing educational research? Is suspect he has, so this is either disingenuous or he has internalised the predictable political stances of education researchers to such an extent that he simply thinks they are a set of obvious and nonpolitical principles. If it’s the latter, that may explain a lot.

The most pompous part is the idea that Joorden’s saw himself as an ‘anthropologist,’ observing this strange species of teacher who do inexplicable things like attend researchED conferences. I suspect that any controversy about researchED is entirely manufactured by those in academia who don’t like teachers organising their own conferences on their own terms. It is not ‘real-world’ controversial.

The discussion of these missive continued on Twitter and led to education researchers playing some of their greatest hits. One of these is ‘positivism’.

The way it is supposed to work is like this: A teacher refers to empirical evidence that appears to support or refute a particular practice. A sophisticated researchers then labels this ‘positivistic’ as a form of dismissal. Sometimes they will say they value positivistic evidence as part of a wider whole, but I don’t find this convincing because the term tends to be used pejoratively.

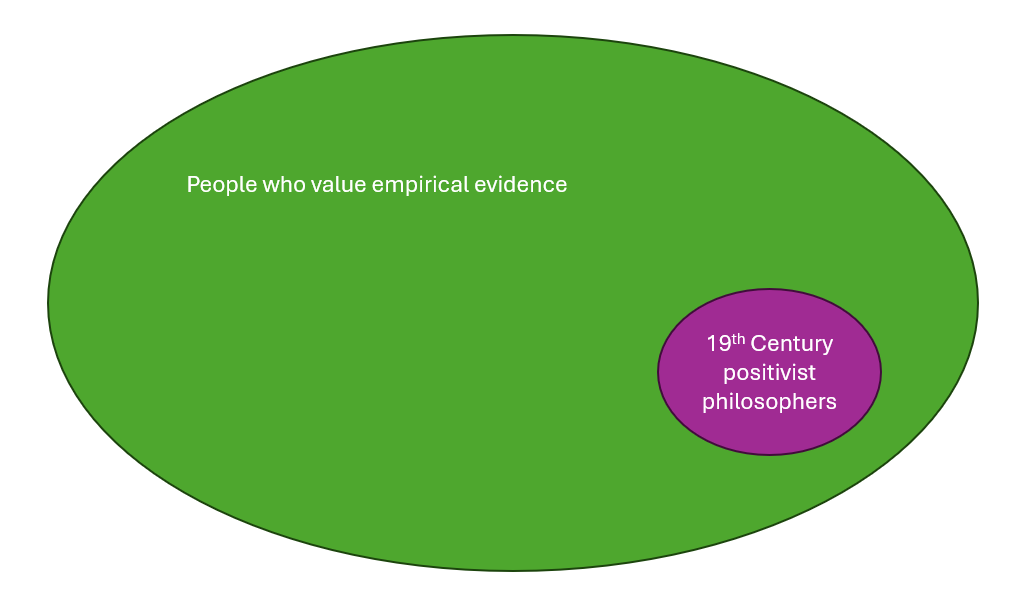

Positivism was a 19th-century philosophical tradition that valued empirical evidence. But that does not mean anyone who values empirical evidence is a 19th-century positivism philosopher. Technically, many of those accused of ‘positivism’ today would probably better fit the category of ‘postpositivism,’ but that’s an aside. So, equating the valuing of empirical evidence with ‘positivism’ is a sleight of hand education researchers tend to use.

The alternative to valuing empirical evidence is to not value it. This is not a good position to hold but it does explain a great deal of education research based on autoethnography, critical theory and so on.

Educational journalism of the week

It is always a good sign when an article about education quotes me, as was the case for an open access article in EducationHQ by Sarah Duggan.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Filling The Pail to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.