This week has been a very busy one. As I put the final touches to this post I am also putting the final touches to my talk for researchED Ballarat today, The Homunculus Paradox. From the program:

“Is there a miniature person in your head, pulling levers and turning dials to control what you do? No? Then why do we often act as if there is and why is this a paradox? What can cognitive load theory tell us about the mind and how it makes use of the knowledge we hold in our memories? What does this model tell us about jokes and what can jokes demonstrate about the way we understand what we read? In this existential session, Dr Greg Ashman will explore these questions and more. Bring your pet homunculus.”

Last week was a long weekend for Victoria’s Labour Day holiday. We took our youngest to Chapel Street, Melbourne to look around the vintage clothes shops. At 15, it is just her sort of thing. However, back in the day, it used to be my thing, too. I even bought a shirt that will be making an appearance today.

It was hot in Chapel Street and that has been a theme for the week. On Tuesday evening, I took my eldest daughter to Melbourne for a talk by Louise Perry, organised by the Centre for Independent Studies. Claire Lehmann of Quillette was on hand to ask the questions. My daughter and I felt underdressed—we had dressed for travelling in hot weather—but we quickly overcame our self-consciousness. Perry is an advocate of a conservative form of feminism and I rightly predicted that my daughter would find the views expressed to be different to those she is familiar with. It made for a great conversation on the train home.

This week’s Curios include retro reading, bad teaching, some offensive comments and much more.

Pundit of the week

It’s me again. I was interviewed by Chris Harris of the Sydney Morning Herald for a story he was writing on new data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)—more later. Harris asked me about mathematics anxiety, a concept that I am not totally convinced is an actual thing:

“Do kids get anxious when confronted with maths assessments or maths problems or being asked to do maths? They probably do, but people get anxious about a lot of things, particularly things that they don’t feel that they’re particularly good at…

You get a lot of this: ‘Let’s address maths anxiety by creating fun activities, by going on excursions, by having guest speakers, by making models of many-sided shapes out of paper and sticky tape and all this sort of thing’…

Now that can certainly be fun. And kids will say they enjoy it because kids enjoy doing fun things, but it doesn’t address the fundamental issue, which is their ability to do maths…

To reduce that … You want to give them the ability to solve the problems, to do the maths, then they won’t feel as anxious about it.”

Harris quotes PISA data that 43% of girls and 33% of boys report becoming ‘very nervous’ when confronted with maths problems.

International comparison of the week

Back in 2016, Scientific American published an article by Jo Boaler and Pablo Zoido that used PISA data to argue that in mathematics teaching, ‘an emphasis on memorization, rote procedures and speed impairs learning and achievement.’

I wrote about this at the time. I could not get to the bottom of the memorisation claim because my reading of the data available on the PISA website did not support it. [There is much more to say about the speed claim and if you are interested then start here].

I remember these things and so it was with interest that I read a new report by ACER—the Australian body that analyses PISA data—the publication of which had prompted Harris’s article.

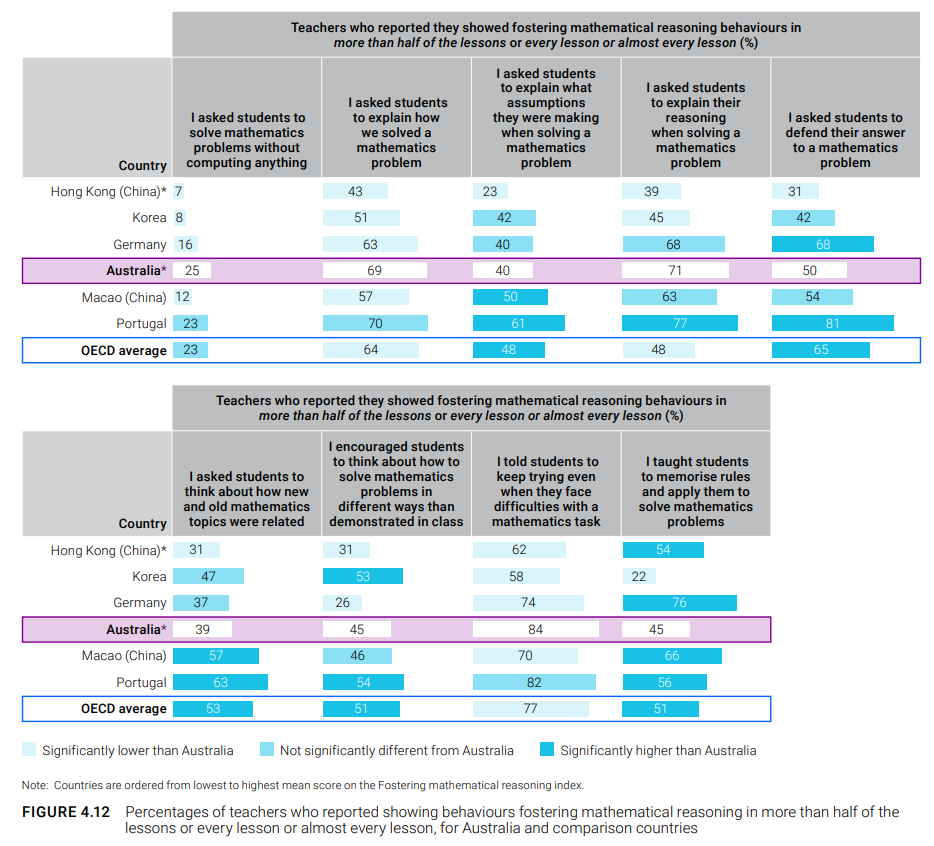

In particular, my eye was caught by Figure 4.12 below:

It seems that Australian teachers report using less memorisation of procedures than the OECD average, including less than Hong Kong and Macao, states that outperform Australia in PISA maths.

As ever, we have to try to imagine how teachers interpret such questions. Progressive education ideology tends to disdain memorisation, often referring to it as the ‘rote memorisation of procedures’. When a teacher demonstrates how to solve a problem and hopes students remember this, would they describe it as ‘teaching them to memorise rules and apply them to solve mathematics problems’ or would they shy away from that description? It’s hard to know.

(Bad) teaching advice of the week

Still on the topic of mathematics, there is much well-intentioned advice that we probably don’t want to pay too much heed.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Filling The Pail to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.